I am not sure where to start.

I suppose the best thing to say is that I could identify the familiar symmetry of Orion at a young age. I viewed it through rustling leaves as a child on camping trips with my parents and grandparents. I looked for it when my Mom signed me up for Boy Scouts, and where I looked through my first tiny telescope at Skymont Boy Scout camp. I marveled at the colors in the nebula during my first viewing through a Dobsonian telescope. I followed its path in the first few days of driving to and from high school, rising in the fall and setting in the spring. I left home for college chasing its direction, south down Hwy 41. It was always there, seemingly inconspicuous. I have always felt a connection to this cosmic way-finder. Big decisions and events in my life came and went, yet those stars seemed to always find their way into my consciousness.

I’ve been told I asked a lot of questions as a child. I still ask a lot of questions. I think this came mostly from my Dad who continually seemed to give me just enough information for me to be interested, but so little that I was forced to figure it out on my own. Throughout the years, I quickly picked up things I had an interest in, and sought to understand the things I didn’t easily learn. I had so many wonderful teachers who opened my mind. I became somewhat voracious in my reading and learning. College was tough for me. I had wonderful friends, great professors, exceptional mentors, and found my wife, Katie, who will always be my brightest star. Soon after college I entered a career with the Episcopal church and have enjoyed it immensely over the last 21 years.

In the Fall of 2011 I returned to photography, thanks to a friend who showed me the wonders of the digital technology. Coming from film, I almost relearned photography as I quickly submersed myself in the hobby. I soon merged photography with astronomy and began photographing the sky. My father-in-law helped me build an astronomical tracker out of Sky and Telescope so that I could take a decent photo of Andromeda. Orion was on the list, but it took me a bit longer to focus on it. I spent most of 2013-2018 driving around Tennessee and Georgia to find dark skies. After a failed start on a mosaic with a different telescope and camera, I took the first image of this 200 image/panel mosaic in 2015 at Fall Creek Falls State Park in Tennessee. This process has cultivated many wonderful friendships over the years, and one of those friendships led me to Marathon, Texas to see some REALLY dark skies. I ended up at the Marathon Sky Park where I now have a telescope installed in Observatory #1, pier #2. It’s been a dream come true. A special thanks to Danny Self for being one of the biggest parts of this project. Without his invitation to MaRIO (Marathon Remote Imaging Observatory), this project would NOT have been possible in this time frame. In three years of traveling, I managed to get 75 images/panels. Still, nothing to laugh at, but in the last three years in Marathon, I’ve completed 140+ images/panels. Another big thanks to Dennis Sprinkle and his friendship. Sometimes you need a friend to tell you when it’s time to quit or keep going, and he managed it perfectly.

And now to the actual mosaic process. Shortly after attaching a DSLR camera to my telescope, I purchased a dedicated CCD camera to utilize every pixel. In no time, I was attaching a CCD camera to my telescope, and soon after, to my digital photography lenses. I set out almost immediately to photograph the region. Not happy or satisfied with my results, it inspired me to continue with higher resolution. In 2015, I began researching the next steps for a new camera. In my research, CMOS cameras were on the horizon but a complete unknown for astrophotography. I had decided on the 16803 sensor and figured it would take me two years to save and purchase. The only problem (and every astrophotographer’s problem) was the sensor size was going to require a larger image circle which would mean a new telescope. Up until this point, my William Optics 132 telescopes had served me well, and William had always been very helpful. So, I decided to stay with my William Optics refractors and started saving for another 383 camera and an Astro-Physics mount as my hyper-tuned CGEM just wasn’t cutting the extra weight of two telescopes. I spent the summer enjoying my first CMOS camera- the cooled 178 camera shooting galaxies on my 132 refractor.

In October of 2015, as Orion began to rise, I decided to revisit the constellation on my 132 with my ATIK and enjoyed shooting M42 and Horsehead that season. In November of 2015, OnSemi announced the KAF 16200 sensor. I waited until some news trickled out (you can no doubt find my questions littered through Stargazers lounge and Cloudy Nights), and I fully committed to this sensor for my project. I made my purchase in March of 2016 and received the camera. Where the above (or to the left) image displayed a 10-11 pixel scale, I was about to embark on a 1.6 pixel scale of the constellation Orion. I was certain this would reveal the true nature of that space- behind the clouds, behind the colors. This would become my ORION Project. Five years. 2,508 individual images. 500+ hours of integration. Lots and lots of patience.

The image posed many problems from the start- balancing differing sky conditions per night, aligning to the same star position each and every night, and meticulously returning to a position just a few thousand pixels North, South, East, or West. Aside from the challenge of software, there were also the continual hardware problems and challenging weather conditions in East Tennessee. Sure, there are some GOOD nights, but there are some NOT SO GOOD nights as well. My fellow astrophotographers and I actually retrofitted ice fishing tents to use as astronomical shelters.

Combined with a Mr. Heater Portable Buddy with a carbon monoxide detector (that we affectionately refer to as “little buddy”), this tent provided a comfortable shelter for me to image through the night. A group of 10 or 12 of us from our astronomical society battled through many nights. It became a game of continual editing, spending endless hours to scour the data and ensure it was usable. Drivers would have to be updated; calibration files would have to be captured; parts would wear out and have to be replaced; but deep down, I knew I had to finish this. I set out to get to certain points so I could create a small(ish) image of my work to tide me over to the next season which included the belt stars, Betleguese, Rigel, the loop, and finally the Witch’s head.

It was during this part of the mosaic that my role as a Director of Youth and this project collided. I take students on a pilgrimage (mission trip) every two years to discover new things and learn about helping others. It’s a very fun trip and a lot of hard work. In 2018, my students decided to travel to San Diego, California to work at a community outreach center all week. We slept on the floors and worked with the homeless community each day. From hair cuts to showers and clothes washing, our students learned how to give back. Another of our side projects was painting a mural on an adjoining wall. Somehow in the process, my image of Orion was selected, and it’s now on the wall of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church in San Diego, California, courtesy of some amazing students. Truth be told, this might be the most amazing part of the project for me. Just another way it all came together through the years.

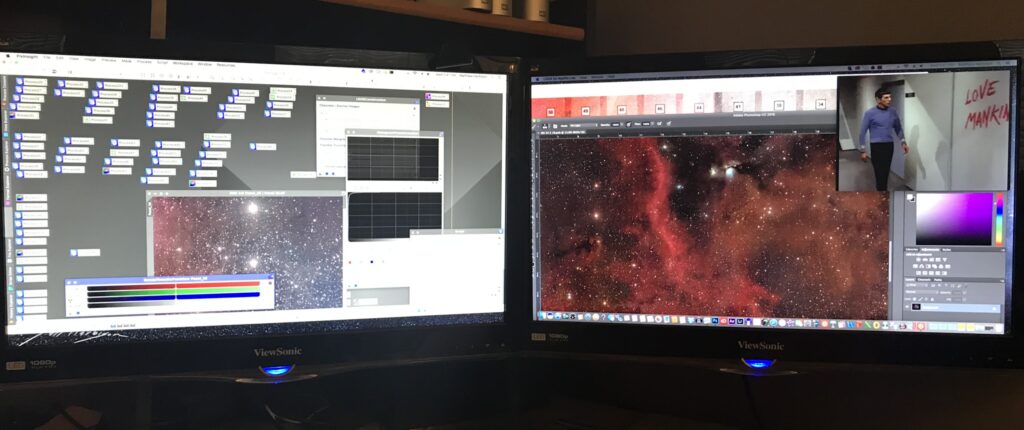

Let’s get back to the imaging stuff. Processing of the data was an immense chore. I began in 2015 on a Mac Pro with 2 Xeon Processors and 64GB of RAM. This machine was easily one of the fastest computers of the day, and it carried me all the way up to panel 47 where I believe I hit the RAM limit of the computer. At this point I got creative and split the mosaic into two pieces. I was essentially working on one part at a time and being careful to carry out the same processes on the counterpart. It was probably not the most scientific way to proceed, but the only way forward for me in 2017. By the time I got to panel 109 I was able to connect Betleguese and Rigel. I ALMOST QUIT here. It was my friend Dennis who encouraged me to keep going.

I entered into another one and a half years of imaging somewhat reluctantly but quickly got on board. By this time, I must say my software suite and hardware had really ironed out the bugs and things were humming along. Sequence Generator Pro provided a way for me to finally create a complete 200 panel mosaic in the framing and mosaic wizard. QHY had the drivers on my 16200 camera worked out, and Pixinsight is absolutely the most robust and amazing software I’ve ever used. Finally, on April 15, 2020, I shot my last panel and had officially collected all of the data. From here I began the long march of data refinement.

The global pandemic hit and was not fun, but I had more spare time than normal as I was working from home. I created masters and solve data for each of my 200 panels creating an archive of over 46GB of mastered data- LRGB master images + a mastered LRBG combined image. Each frame was solved with the solution retained in the xisf header. I had massive amounts of data to work with as I organized and calibrated. Finally, I attempted one last solving and registering on my Mac Pro before throwing in the towel and building a new computer. The registration process from the mosaic by coordinates tool took a total of six days. It did complete, but there were errors in the frames from what I can only guess were RAM issues. The gradient merging failed after an additional four days. That’s when I decided to start saving money to build a new computer. While waiting, I reached out to one of my former students to create a “soundtrack” for the image. I had always thought of it being presented in such a way that would draw people into its depth, and I felt music was key. Jonathan Burkette of local music group “5 on 7” created the custom track you hear if you press the play on the audio bar- “Spacetastic”. Fast forward to August 2020, and the new computer is finished. The new computer is an AMD Threadripper with 24 cores and 256GB of memory. It took a total of 23 hours to provide an astrometric solution for all 200 panels and then an additional 19 hours to merge into the gradient merge mosaic tool.

The project amasses a total of 44 TB across 21 hard drives, 7 laptops, and 3 desktops, with my 4th and final desktop recently completed. I am still trying to decide what to do next. I would love to get this data into the hands of students. I’m not naive enough to think it’s research quality, but it is a LOT of data that might just be helpful. To that end, please let me know if you have some ideas.

The countless hours of imaging, editing, calibrating, and sometimes just flat out persevering really had me wondering why I just didn’t quit. I mean, my image isn’t a life or death issue. It’s not going to provide world peace. So why? Why am I putting myself through all of this headache? Well, as I look back, wow, was it fun. I had my moments, but isn’t that just like life? I had my wife, my family, and my friends to encourage me. Sometimes, it was their encouragement and patience that kept me from quitting. To speak to the patience my wife has had with me, it’s been unfailing. She occasionally made a nerd joke or three- which I’m OK with, but she absolutely encouraged me. Another important part was my astronomical society (the Barnard Astronomical Society of Chattanooga) whose members continually checked up to see how I was progressing. They would ask me if I enjoyed photographing the SAME THING EVERY NIGHT, while secretly I know that they were jealous at my opportunities to image every night.

I’m happy to share it with you.

And so it’s here that I say, “THANK YOU!” I’m incredibly thankful for everyone who put up with this project. My family wondered why I’d fall asleep in the afternoon. My sister-in-law created an Instagram account dedicated to my uncanny ability to fall asleep or nap anywhere in the middle of the day. My co-workers and friends have had to hear about my most recent space or science discovery EVERY DAY OF THE WEEK. I’m sure it got old, but thank you all for being a part of the journey.

I extend great accolades and thanks to my cousin, Brian, who was absolutely my sage. When I had questions about power, I called Brian. When I needed to brush up on coding, I called Brian. When I had a network problem, I called Brian. It helps to have geniuses around! And lastly, thanks to the people who read this write up. It’s been stressful and frustrating at times, but I’m thankful, so THANKFUL for the opportunity. I guess I just want you to know that I don’t take any of this opportunity for granted.

This is a small part of space, and it belongs to everybody. I just had the pleasure of photographing it.

Thanks for the opportunity!

Matt